Grace and peace!

This week, and every week:

May we challenge one another’s perspectives with compassion.

May we open our hearts and minds to learning.

And may we build a community that is mutually supportive.

Voices Gathered at the Table

One of the most important things we can do in our first moments of conversation is to take note of who is present at the table. In other words, who is participating in the dialogue? This is an important question because when the vast majority of voices at the table belong to people who identify as English-speaking, native-born (meaning born in the U.S.), white, and/or Christian, chances are it will become a conversation about immigrants that doesn’t really include immigrants.

Which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It certainly isn’t the job of every immigrant in our community to teach the rest of us about migration causes and the U.S. immigration process. As a member of the majority culture (English-speaking, native-born, white, Christian), I will certainly turn my ear to the voices of those who have lived migration experiences and who are willing (and ideally getting paid) to share those experiences with me.

Yet it is my job, and my job alone, to learn.

That being said…

When immigrant voices are distinctly lacking from the table, their stories and their experiences are often misunderstood or misinterpreted. And when conversations lead to actions, the silence of these precious voices echoes lament into every heartbreaking corner of the U.S. immigration system.

Which is why I want to make sure, to the best of my ability, that there is room at this table for immigrant voices who feel safe or brave enough to sit with us (though please know it’s okay if you don’t). And for those of us who identify within the majority culture, I ask that we honor the dignity of immigrants living among us by making the space and the effort to sit with them. I also ask that if no immigrant voices are present, for whatever reason, we would remain cognizant of how the lack of their voices will affect our conversation.

What Makes a Story (or a Fear) “Credible”?

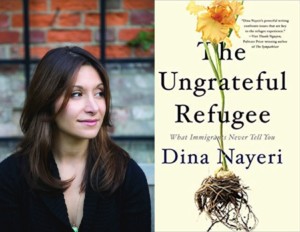

In her book The Ungrateful Refugee: What Immigrants Never Tell You, Dina Nayeri (an Iranian refugee) asks the question, “At some point, is it so hard to believe that home isn’t an option?” (255). So often asylum seekers are deported because their stories of trauma and fear were deemed incredible (and not in a good way) by Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS) officers. This disbelief of immigrant fears and stories also pervades our society as a whole.

In her book The Ungrateful Refugee: What Immigrants Never Tell You, Dina Nayeri (an Iranian refugee) asks the question, “At some point, is it so hard to believe that home isn’t an option?” (255). So often asylum seekers are deported because their stories of trauma and fear were deemed incredible (and not in a good way) by Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS) officers. This disbelief of immigrant fears and stories also pervades our society as a whole.

One of the most poignant failures of our immigration system is the blatant (and blissful?) lack of societal awareness around the immigrant experience. Which is incredibly ironic, given that (apart from indigenous peoples) we are all descendants of immigrants ourselves. I know I’m not alone in this kind of immigrant amnesia. Much of the time I think of myself as a native-born U.S. citizen and therefore not an immigrant. Yet I am a descendant of Germans, mixed with English and Scotch/Irish blood. There was a time, however long ago, when my ancestors immigrated to this country.

This amnesia fails us when our collective lack of understanding leads to dangerous outcomes. Not least of which being when an immigrant “fails” their Credible Fear Interview (CFI), are thus deported, and are then killed upon returning home. The CIS officers conducting these interviews rarely have any genuine understanding about immigrant experiences. And they are often coming from a place of power, steeped in Western culture and politics with the leeway to interpret the immigrant’s story in whatever way they see fit.

To be clear…

This conversation is not an attack on CIS officers, though it is a conversation that requires us to recognize the underlying perspectives of all people, along with the reality of our immigration system. The reality is that the officers hired to enforce immigration laws (and the legislators who write them) are often unaware of the role their personal perspectives play in their decision-making. And regardless of this reality, they are put in charge of interpreting the “credibility” of the stories of black and brown immigrants who have suffered torture in underdeveloped countries controlled by dictatorships.

Which leaves traumatized immigrants trying to prove that their fear of returning home is sincere and that their story is reliably consistent, even though “sincerity” means different things to different cultures and life is full of inconsistencies.

Sadly, the need to prove their fear doesn’t end with CIS officers. Even if immigrants “pass” their CFI, the reality of our collective lack of understanding means that we native-borns are quick to distrust immigrants from the outset. We hear the message to distrust immigrants via social media platforms. We hear the message in the rhetoric of our political leaders. We are told, time and again, that immigrants as a whole are criminals, invaders, and even terrorists. And we can’t assume that this message doesn’t affect the CIS officers’ ability to objectively decide whether an immigrant’s story is “credible.”

Just Imagine…

Imagine what it would feel like to be sitting on the immigrant’s side of the table. Imagine having fled a war-torn or destitute home with few provisions. Imagine having traveled thousands of miles, most of them on foot, through what can be dangerous terrain. Imagine approaching a giant wall and asking heavily armed, foreign-speaking officers for asylum in the U.S. Imagine being arrested and taken to prison while processing takes place.

Imagine sitting before another foreigner, a complete stranger in all the ways that one can be a stranger. Imagine having to relive highly traumatic events with that stranger through the act of storytelling, even though the suffering is still unprocessed and raw.

“At some point, is it so hard to believe that home isn’t an option?”

Respect Through (Non-Exploitative) Affirmation

Gratefully, most of us don’t have to make the impossible decisions about whether or not an immigrant’s fear is “credible.” Instead, we are able to relish in the triumphant stories of immigrants’ harrowing journeys to the U.S. and their success in building a new life here. Amid the sorrowful tears that we may shed for what these people have gone through, we are able to smile and shed joyful tears while listening to how they were resilient in overcoming every obstacle. We love these gallant stories, so much so that there is now a market for immigrant literature.

Which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It means in part that native-borns are wanting to listen and learn about the immigration experience. Yet even in our desire to believe these inspirational immigrant stories, there lurk dangerous outcomes. Not least of which being that we want to rush out and help them without first getting to know them. We want to be a part of their story, though in doing so, we diminish the immigrant’s voice by (however unintentionally) placing ourselves front and center in their narratives. Or we focus so much on the positive outcomes of a few that we forget that millions more are stuck in asylum limbo, trying to earn their right to safety in the U.S. by proving that their fear is “credible.”

My challenge for all of us (myself included) is to find the middle ground between approaching an immigrant’s story with distrust and approaching it with a desire to help and/or feel good. How can we native-borns sit with our immigrant neighbors at the table and affirm their experiences as valid and profound without making them about us? Are there ways that we are doing this already?

Now It’s Your Turn!

In the comments below, I invite you to ask questions or share any first-hand experience(s) you might have.

I also invite y’all to reflect as a group on the questions that I posed:

How can we (native-borns) sit with our immigrant neighbors at the table and affirm their experiences as valid and profound without making them about us (how we feel or how we can help)?

Are there ways that we are doing this already?

I really like the organization and the good job they always do

Thank you for your support, Sulemana!